What's your function?

The seminal seminar on simple

Jul 9th, 2020 · 5 min read

Note: This article is a written companion to the following video about functions from my brand new barely functional dev channel.

My programming career has taken several turns; however, none of them have been as abrupt or consequential as my recent love affair with functional programming. I already wrote my very first post about one chapter in that journey. Before that, I was captivated by the allure of what functional programming had to offer, but I didn’t fully commit to using the paradigm until an opportunity came up to start a bold new frontend project giving me the freedom to adopt new technologies and paradigms.

Selling the project to the right people would put me much closer to the cutting edge of technology and provide the freedom to experiment with different design patterns that (while not exactly new) were fresh, thriving, and more in line with my philosophy. I joined the community at a time when functional programming was going through a new renaissance. Practiced modern artisans shared their craft with the world in the form of great content explaining functional programming. This content allowed me to learn, convince, and eventually train the skeptics and new practitioners, and I am very grateful for them.

I would like to give special recognition to @mpj of Fun Fun Function, which has been especially useful to me along my journey. Thanks to your videos, I started feeling more comfortable in JavaScript and started contributing to frameworks like Hyperapp and eventually publishing libraries with my ideas. That experience helped me land my dream job where I get to hack on a functional frontend framework. Now I’m doing my part to pay it forward, sharing my knowledge by writing these posts, giving lots of technical talks worldwide, and finally launching my new channel after lurking and taking notes for years. It was bittersweet timing to hear that @mpj is now moving on to something else (see below). I wish you all the best and enjoy the next chapter in your life.

it’s all functions and games

I noticed a gap in other functional programming materials that I’m going to fill in with the wisdom I have collected during my experience. It’s often assumed that devs new to functional programming will understand what functions are and how to think about them. At best, you might get a dictionary-style definition of what makes a function pure or some example functions, but this is missing context explaining the relevant philosophical background and the correct mental model to use when learning functions.

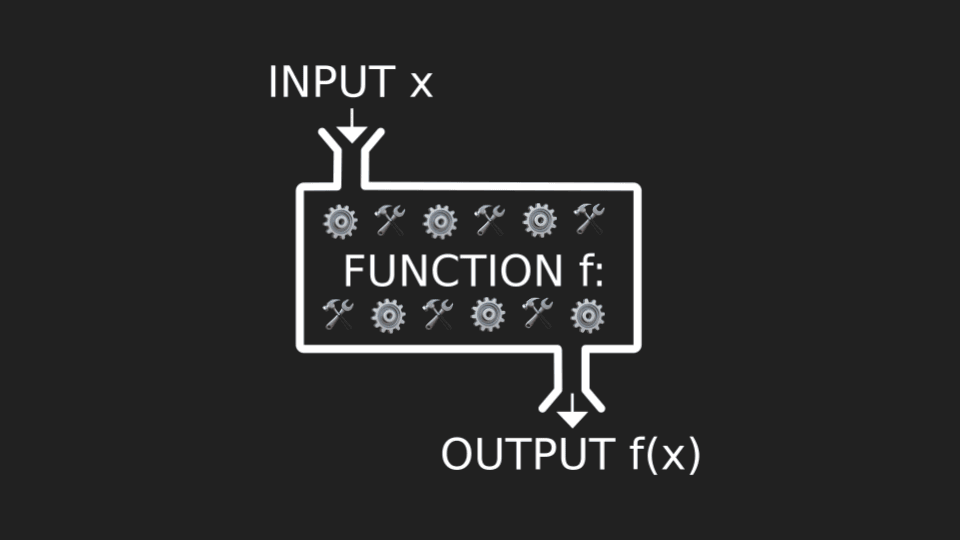

A common approach for explaining functions is to start with input at the top. That input feeds into the function, some magic happens, and then output comes out the bottom. The danger comes in explaining the magic connecting the input to the output. An analogy I frequently come across is that of an assembly line in a factory. This type of thinking is treating our function as a machine.

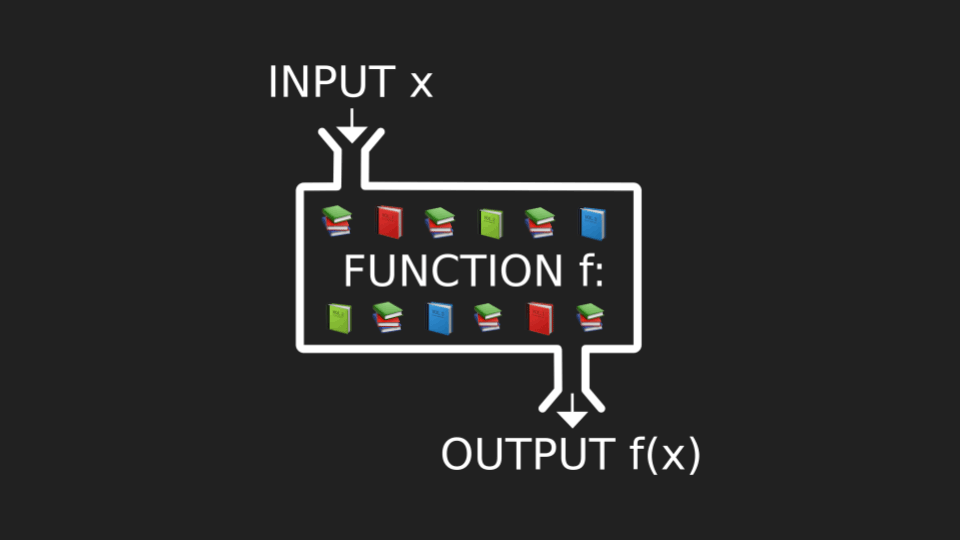

This analogy is somewhat accurate, but also dangerous for someone new to the concept. I’ll be explaining why in a bit, but first I’d like to offer my alternate approach: think of a well-organized library. In this library, the input tells you exactly which shelf to visit, which book to pull off that shelf, and finally which page to turn to in that book. The contents of that page is the output.

A library may seem like a strange way to think about functions. To help explain it, I need to give some background on what functions represent mathematically. If you’re already having painful flashbacks to Mrs. Smith’s algebra class, don’t worry. I will be very brief, only covering high-level information, and there won’t be any quiz at the end.

ready, set, compute

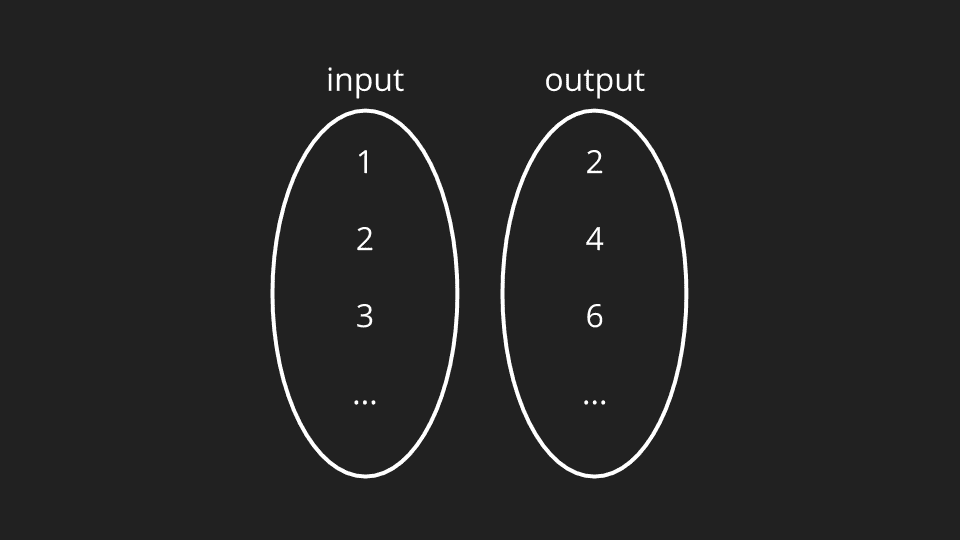

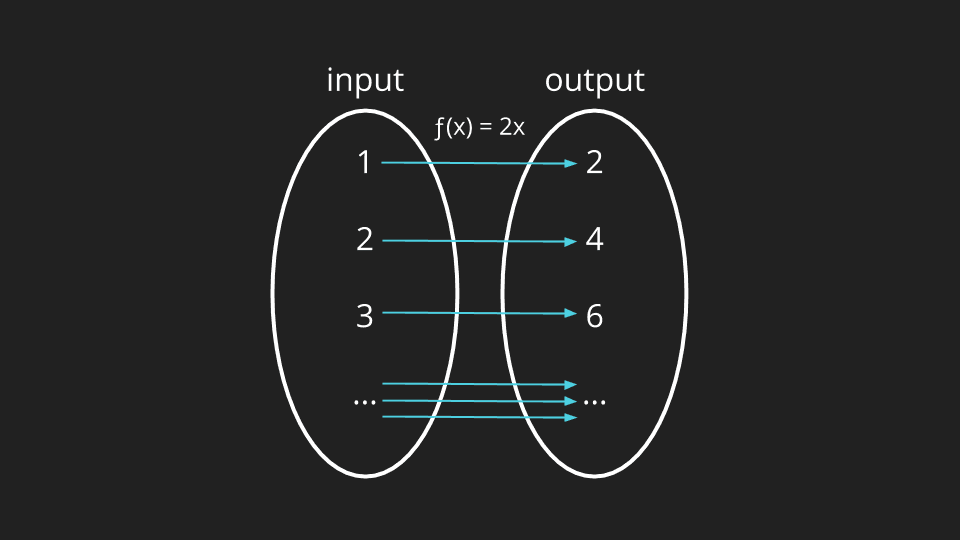

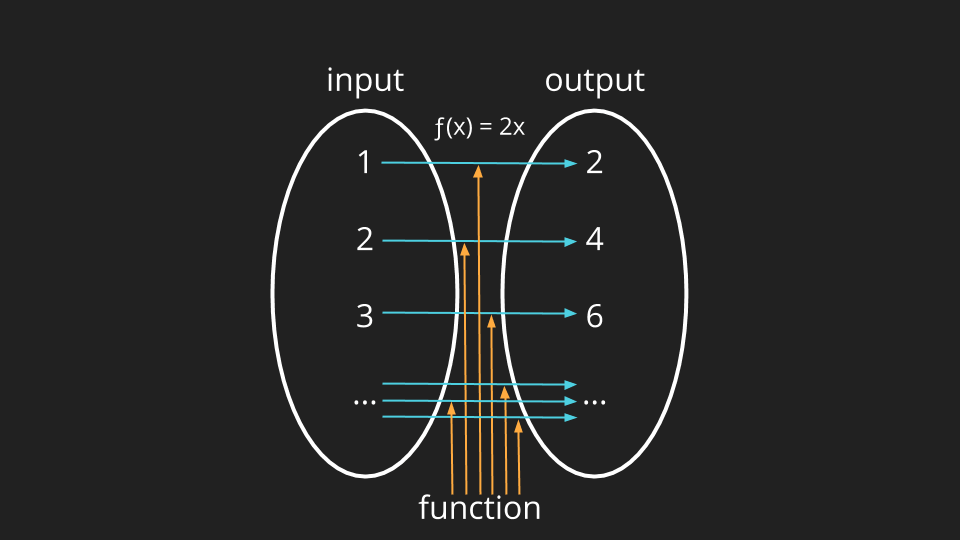

Let’s start with a set of all valid inputs that can be fed into our function (shown below on the left) and a second set for all possible output values spit out by our function.

To build the relationship between the inputs and outputs (the magic we talked about in the first diagram of a function), we just need to add some arrows.

These arrows show how the input and output sets are related. In this case - each input is multiplied by two to produce the corresponding output. It’s important to note that these arrows are what define the function.

Math class adjourned.

a dose of reality

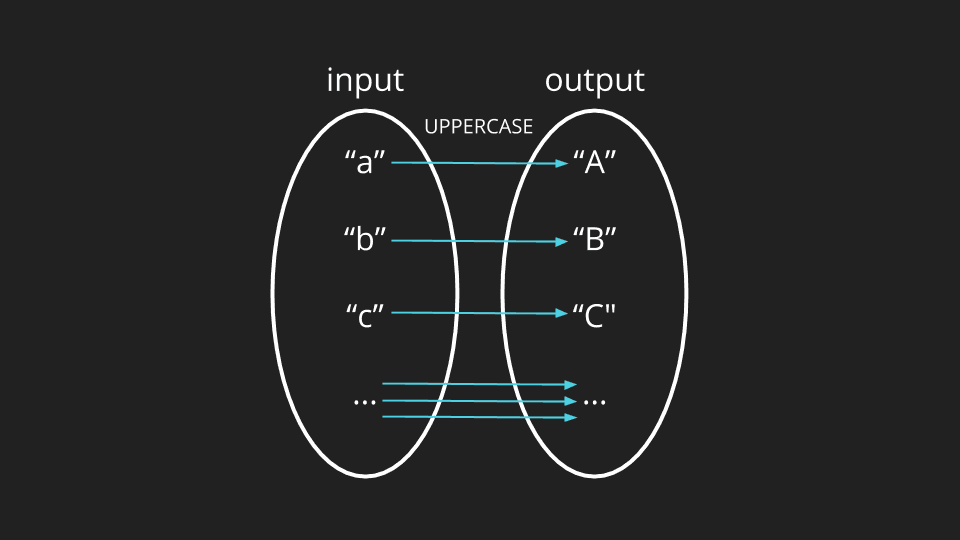

Next, let’s migrate back into the world of computer science. The concept isn’t limited to numbers (which is what this notation is typically used for) but applies to other types of values. In the world of computers, we frequently care about types such as strings, for example.

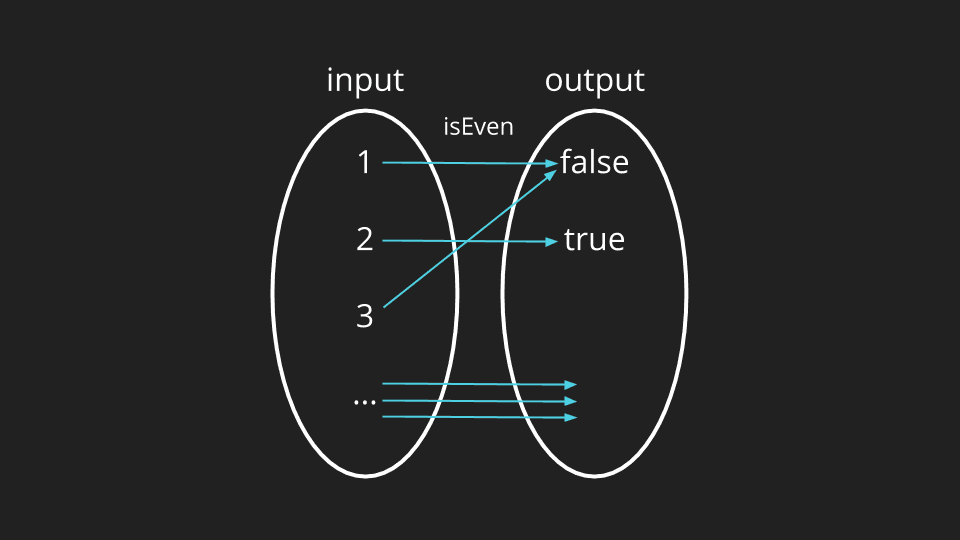

For this function, the input is all possible strings, and the output is the uppercase equivalent for each input. In addition to mapping between values of the same type, we can map from one type to another. For example - let’s say our input consists of numbers again, but we map them to boolean values true or false.

Here we are mapping whether a number is even or not. Thus 1 maps to false, 2 to true, 3 maps to false, and so on alternating forever. While it is perfectly valid to have multiple inputs map to the same output, it is not valid to map a single input to multiple outputs. This rule is why random number generators don’t count as functions, because they produce different output values given the same input.

codified concepts

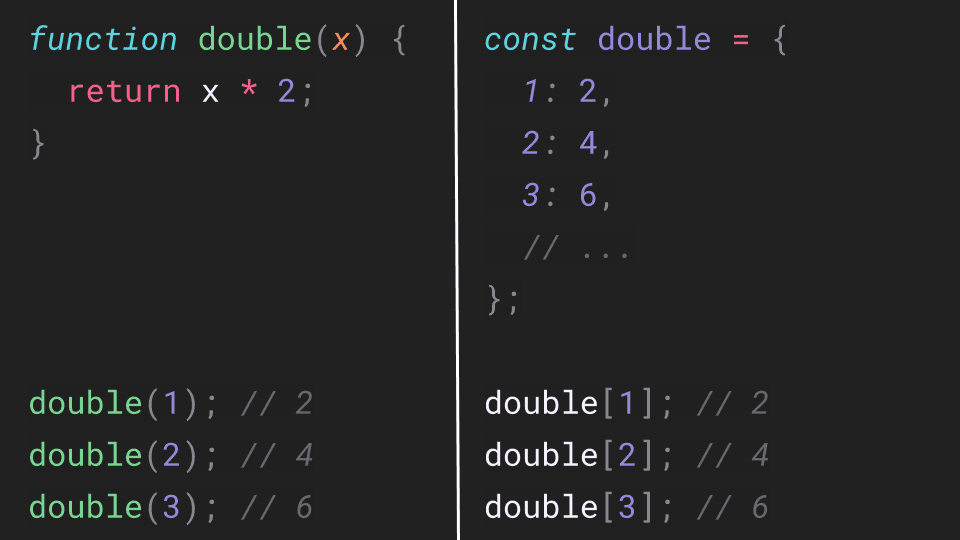

Now let’s complete our journey back to the world of software by looking at some code. Take that first function we talked about, which takes in a number and doubles it.

function double(x) {

return x * 2;

}

double(1); // 2

double(2); // 4

double(3); // 6

You can call this with various values and see that the results match our expectations. While straightforward to understand, this is the code equivalent of thinking of our function as a machine that does things.

How would we think of the code in terms of the other approach where we map from input to output instead?

One way to represent this mapping is with an object, as shown above on the right. The keys are the inputs (the x in the code on the left side). The value for each key is the result of calling the double function. This lookup table of all the mappings defines our function. Instead of calling our function, we perform a lookup and immediately get the result. The lookup is our library, and our input tells us exactly which one of these books to open, and then the page we open up will tell us what the output is.

This mental model is essential for understanding pure functions with no side effects. The object mapping representation severely limits what we can do, in a good way. No code will execute when we use the mapping to lookup a value. That means we need to behave as if we’re able to pre-compute all the values. This philosophy guarantees no references to anything else for reading or writing. Also guaranteed is that we will always get the same value, like the arrows in our set representation function. Because we need to treat this as if we know all the values ahead of time, time is no longer a factor, which means that when the function is called doesn’t matter, hence avoiding race conditions in code that uses this style.

We also get more control and automation around how to optimize code execution. Usually, the object representation isn’t what the machine would use for execution, but conceptually how the humans think about it. However, if it’s expensive to compute the result of our function, the machine could keep a cache of those results very similar to our mapping, and not worry about when to invalidate it because the mapping always holds true. If the input to the function is known ahead of time, it’s possible to run a code transformation that replaces calls to the function with the result already known. It’s important to note these optimizations (and more) can happen automatically by treating functions, like functions.

class dismissed.