Hyperapp for Redux refugees

How I learned to stop worrying and love the function

Feb 14th, 2018 · 16 min read

I love Redux.

It was my gateway to functional programming, and the first such code I ever put into production. Gone were the days of using the DOM for storing your application state and precariously manipulating it with jQuery.

Redux provides a tidy state management solution that lives entirely apart from your view. The view becomes a derived representation of the state that is capable of expressing actions the user performs to apply against that state. The actions don’t directly modify the state. Instead pure functions known as reducers are written to take the previous state and description of the user action to produce the next state value. This immutable state updating approach takes inspiration from The Elm Architecture, unidirectional data flow, and Flux.

Redux is a tool extremely focused on doing one thing well. It is possibly the most popular JavaScript implementation for immutable state updates that exists today. Because Redux is so focused on the state, it is modular enough to work with many different view libraries. React takes a similar focused approach with your view, providing an efficient virtual DOM algorithm that can be plugged into the browser DOM, native mobile apps, VR, and likely more to come. Because of this, building a robust web application following this architecture will require assembling separate libraries for integrating Redux with React and the target for rendering React on.

Hyperapp is a single library performing two functions that work well hand in hand with one another. It provides a concise form of immutable state updates similar to Redux/Elm combined with a balanced subset of the virtual DOM functionality you would find in React and its peers. Hyperapp embraces idiomatic JavaScript customs and norms. It holds firm on the functional programming front when managing your state, but takes a pragmatic approach to allowing for side effects, asynchronous actions, and advanced DOM manipulations (more on those first two later). Hyperapp provides a powerful abstraction for building web apps, while still giving you access to enough “bare metal” to avoid limiting you along the way. In short:

Down for the count

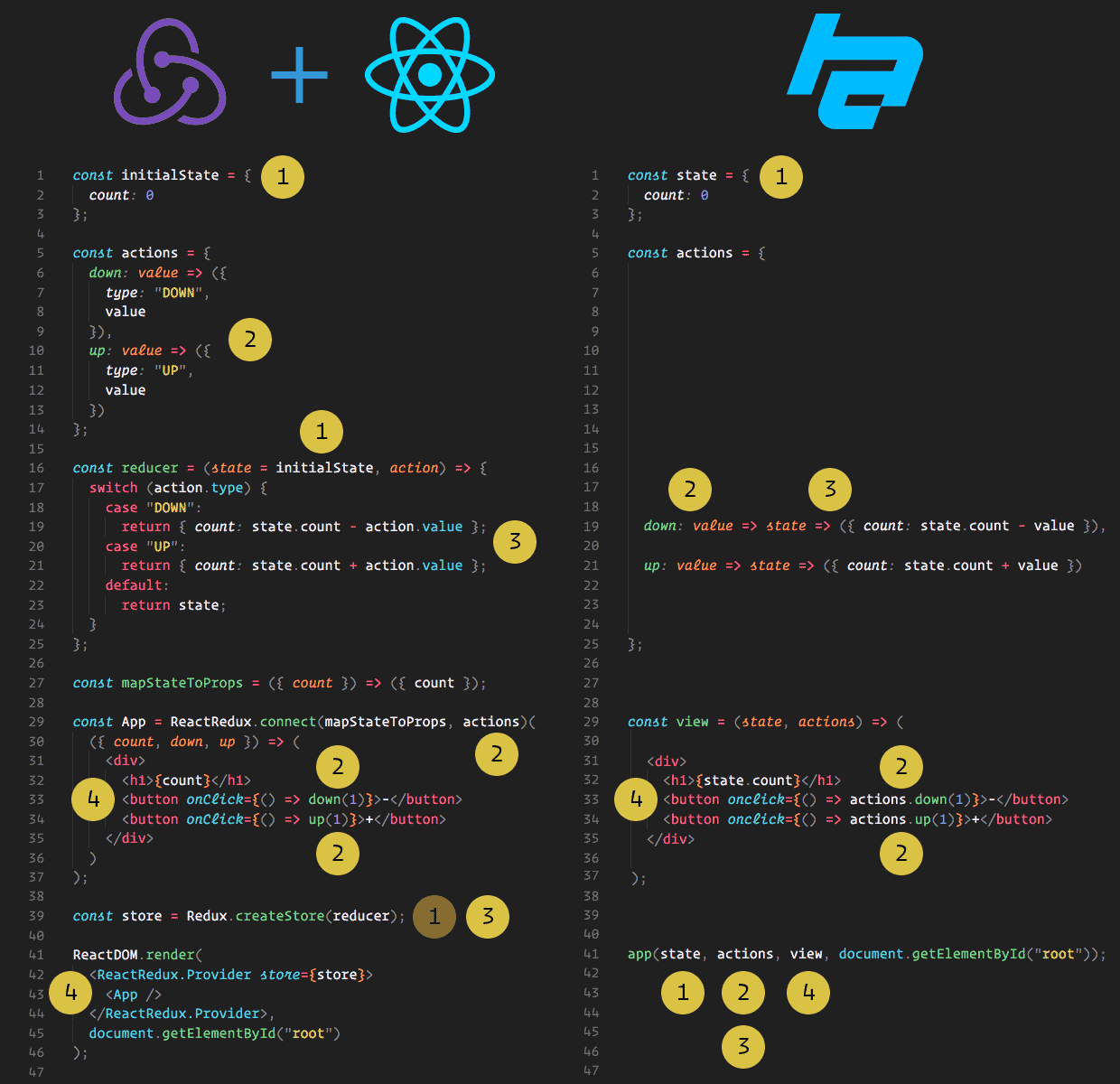

Here is the code for a simple counter app in Redux/React and Hyperapp shown side by side in an idiomatic style for each. The Hyperapp version on the right has spacing added to line up equivalent code as much as possible with the Redux version on the left.

Lets take a look at each of the numbered building blocks of this application one at a time:

- State: in Redux - the state can be of any type, although it is highly recommended it be serializable, and an

Objectis chosen the vast majority of the time. This initial state value is typically used as a default value for the state argument to your reducer.

Not pictured: theRedux.createStorecall optionally accepts your initial state as its second argument.

In Hyperapp - the state is always anObject. Instead of two different ways to provide the default state value, it is always passed as the first argument to theappfunction. - Actions: in Redux - action creators are functions that return actions as plain JavaScript objects. These action creators are usually connected to the Redux store using

bindActionCreators, either directly or automatically using themapDispatchToPropsargument toReactRedux.connect. Actions are usually defined as multiple exports from a single file which are then pulled in under one namespace usingimport * as actions from "./actions"style syntax when using ES6 modules.

In Hyperapp - action creators are not needed since actions already receive a payload representing any data associated with that action. Actions are also automatically wired in to your Hyperapp, so no need forbindActionCreatorseither. Actions are defined within an object where each property is the name of the action function used when it is time to fire one of those actions. - State Updates: in Redux - state updates are performed by reducers, which are pure functions that take the previous state and an action and return the next state. Any action is able to update state in any reducer, which normally decide what state update to perform using a

switchstatement (or other similar pattern matching) based on action type.

Redux uses this signature:(previousState, actionData) => newState

In Hyperapp - actions pull double duty to define what would be the names of the action creators in Redux with a curried version of a reducer.

Hyperapp uses this signature:actionData => previousState => newState

Not pictured: Hyperapp does a shallow merge of the state your action returns with the existing state so instead of having to remember to spread/Object.assignover the existing state similar to:{ ...state, key: "value" }simply return:{ key: "value" }.

Also not pictured: Hyperapp supports an alternate action signature that doesn’t need your previous state in order to compute the new value. This version is not curried like the previous one, since it only uses the data from your action, acting like a state setter function.

Here is that signature:actionData => newState.

Not pictured, the third: the curried function for performing state updates receives a second argument with an object of action functions that you may use to call other actions from inside actions. The full signature is therefore:actionData => (previousState, actions) => newState. This may be used as a replacement for Redux actions that affect multiple slices of the state. - Views: since Redux doesn’t provide the view layer in your front end stack, the view must be manually wired to your state and actions using something like the

ReactRedux.connectHigher-Order Component (HOC) that wraps your existing component for connecting it to the Redux store. In order to use this, you must also wrap your entire application in a<ReactRedux.Provider>that makes your store available to any components that wish toconnectto it. The props mapped by yourmapStateToPropsandmapDispatchToPropsarguments toconnectare combined with all your other component’s props in the same namespace.

In Hyperapp - your state and actions are automatically wired to your view and provided as separate arguments. This wiring only happens in your top level view and the user is then responsible for plucking out and passing around the relevant portions of the state and actions that are needed. For further information, see the section on selectors.

Bonus topics

Slices 🍰

As applications mature over time, so do the needs of their state. It is helpful to break down a large monolithic state object into different subobjects, each of which act as an isolated namespace that only operates on that “slice” of the overall state. The results of each state update for a given slice are merged with other siblings at the same namespace, resulting in a new overall root state object. As far as each of the different namespaces is concerned, its slice of the state is all the state in the world, and so they may be developed independently from one another.

Redux and Hyperapp both support state with nested namespaces, however they do this through somewhat different approaches. In Hyperapp this comes built-in, but with Redux there is some assembly required.

Redux provides the combineReducers higher-order reducer helper function that accepts an object where the keys are state namespaces and the values are the reducers for managing that slice of the state. A new reducer is returned by this function where each of the combined reducers is called for every action with its slice of the overall state. The return from each combined reducer is used for that slice of the resulting state, and thus a new combined state for your app is born.

Now it’s time for an example of how to use combineReducers, and the resulting state shape:

const potatoReducer = (potatoState = initialPotatoes, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case FRY:

// ...

}

}

const tomatoReducer = (tomatoState = initialTomatoes, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case GRILL:

// ...

}

}

const rootReducer = combineReducers({

potato: potatoReducer,

tomato: tomatoReducer

})

// This would produce the following state object

{

potato: {

// ...potatoes

// and other state managed by the potatoReducer...

},

tomato: {

// ...tomatoes

// and other state managed by the tomatoReducer...

// maybe some nice sauce?

}

}

A Hyperapp example with equivalent slices can be made simply by nesting objects inside your state and actions app arguments:

const rootState = {

potato: {

// ...just potato things

},

tomato: {

// ...just tomato things

// maybe some nice sauce?

}

};

const rootActions = {

potato: {

// these actions receive only

// the potato state slice and actions

},

tomato: {

// these actions receive only

// the tomato state slice and actions

}

};

Multiple levels of combineReducers may be used for nesting Redux reducers for state slices in namespaces one at a time, as deeply as your heart desires. Hyperapp state and actions support this out-of-the-box for any level of nesting objects without any such extra syntax.

Actions and state updates are correlated one-to-one, instead of allowing a single action to update multiple slices of your state. While this may seem limiting at first, it’s a Redux feature that I find isn’t often used, and it encourages cleaner organization for state and actions. If you want an action to update global state, it must be located at the root level of the action tree object.

Selectors 👌

Selectors let you define derived state values. Reselect is a library built for writing composable memoized selector functions for use with Redux. Reselect doesn’t depend on Redux, and could very easily be used with Hyperapp if you like it and want to keep using it. However the usage of Reselect selectors with Hyperapp would be quite different, since Reselect was originally written as a utility belt for building mapStateToProps functions for passing to the ReactRedux.connect HOC. Hyperapp doesn’t need any such special apparatus since your view is given the entire state, but you might want to use selectors to get memoized derived slices of that state for passing to your components.

Since there is no magical context built-in to Hyperapp like ReactRedux uses for passing around the Redux store, the flow of state and actions in your application are always explicit. The place where you would do the job of mapStateToProps and mapDispatchToProps is in your view function. It is passed your entire state and all your actions so you can pluck out whatever you want from those for passing as props to your components. The major difference from connect is that you only get a single place to do this, instead of in each component.

Because Hyperapp components are simple pure/stateless functions, if you need to pass state or actions more than one level deep in the component tree, you will need to pass them along as props. If your state and view hierarchies are similar, this is very straight forward. If not, then you’ll probably want to build up tools for writing your view such that you can pass around state and actions without the boilerplate of passing them as props deep to all your components.

Middleware 🔌

Middleware is the suggested way to extend Redux with custom functionality. It allows you to inject logic before your reducers by wrapping your Redux store’s dispatch function. Multiple middleware may be composed together, where each middleware requires no knowledge of what comes before or after it in the chain. The applyMiddleware function is what performs the composition of middleware for Redux.

Hyperapp actions come prewired to their state updates, with no injection point there betwixt. Instead the solution is to wrap your original actions with logic similar to what would be performed by Redux middleware. You could do this manually for every single action if you wanted, but it would be more convenient to write a helper function that takes your actions object (potentially with deeply nested slices) and returns a new object with the same namespaces and functions that call your original actions wrapped with your middleware-like logic. I like to think of such a helper function as an actions enhancer. This enhancer could be manually applied by the user to their actions, but perhaps it relies on adding new actions which require new initial state and possibly even new functionality in the view to work correctly.

Instead we could choose to wrap the entire app function from Hyperapp. Each one of these Higher-Order App functions (aka HOA) will take the next app function and return a new version of app. This new version will accept the previous app’s arguments and call the next app with the enhanced versions of them. This means that HOAs are composable like Redux middleware.

Apps all the way down

Apps all the way down

HOAs are somewhat similar to Redux store enhancers that wrap the createStore function. Wrapping the integral app function gives you the ultimate power to add any functionality that remains compatible with the rest of the Hyperapp API. HOAs are extremely powerful, and must be given all the respect they are due.

One simple example of an HOA is hyperapp-logger, which prints information to the console when any of your actions are called:

withLogger(app)(state, actions, view, document.body);

Notice how withLogger() returns a function that is called with the familiar app function. This returns another function that you then call the same way you would the original app.

In addition to the normal rules of function composition, remember that your HOAs must be composed before calling them with the final app function to use in the chain of HOAs:

// Manual composition

hoa3(hoa2(hoa1(app)))(state, actions, view, document.body);

// Or with a standard-issue compose function

compose(hoa3, hoa2, hoa1)(app)(

state,

actions,

view,

document.body

);

// Compose plays nicely with using different HOAs per environment

const hoas =

NODE_ENV === "production" ? productionHoas : devHoas;

compose(...hoas)(app)(state, actions, view, document.body);

Effects 🔮

Redux has a fairly strict philosophy when it comes to handling side effects:

“Redux is inspired by functional programming, and out of the box, has no place for side effects to be executed. In particular, reducer functions must always be pure functions of

(state, action) => newState. However, Redux’s middleware makes it possible to intercept dispatched actions and add additional complex behavior around them, including side effects.” - Redux docs

Hyperapp takes a more pragmatic stance on side effects:

“Actions used for side effects (writing to databases, sending a request to a server, etc.) don’t need to have a return value. You may call an action from within another action or callback function. Actions which return a Promise,

undefinedornullwill not trigger redraws or update the state.” - Hyperapp README

Here’s an example of how to use this Hyperapp feature:

const actions = {

upLater: value => (state, actions) => {

setTimeout(actions.up, 1000, value);

},

// Called one second after upLater

up: value => state => ({ count: state.count + value })

};

The Hyperapp approach makes integrating with existing APIs (such as the venerable fetch built into many browsers these days) far more straightforward. However this convenience does come with a cost. Logic involving side effects is inherently more difficult to test than pure functions are. You will be stuck with trace level debugging when troubleshooting issues. Readers of your code (including future you) will struggle to understand the control flow of your code containing side effects.

An alternate approach is to instead serialize your side effects as data. This comes from The Elm Architecture, which inspired both Redux and Hyperapp. It follows logically from the concepts already in place. Actions are a way for representing one very specific side effect (user interaction) as data. Immutable state updates are any even more basic form of effects as data where the side effect is to mutate the state by merging with the updated state data returned. By extending this concept one level further, it’s possible to use data to describe any potential side effect using a combination of the data needed to perform that effect and what action (if any) to perform next. This declarative approach of using code as data will likely feel comfortable to any former Lisp users.

I’ve released a library called hyperapp-fx to enable using effects as data within Hyperapp. It ships with support for a collection of commonly used side effects, and the ability to add your own custom effects.

Here is a small example that uses hyperapp-fx to make an HTTP GET request to /data and sends the results to the dataFetched action:

import { withFx, http } from "hyperapp-fx";

const state = {

// ...

};

const actions = {

foo: () => http("/data", "dataFetched"),

dataFetched: data => {

// data will have the response from /data

}

};

withFx(app)(state, actions).foo();

Above you will notice the withFx HOA has been used to wrap our app and run effects when they are returned from actions or bound to handlers in our view. The call to http(...) does not actually make any network request, instead it returns data that describes what request to make later, when that effect is run. You can call http as many times as you like and it will always return the same effects data for the same arguments. This means that http is a pure function! It also no longer suffers from the testing or debugging issues with an implementation that uses side effects in app code.

What’s next?

If you’re already sold on Hyperapp, and have an existing Redux/React app you would like to port over, I have some good news for you. And if that app happens to use create-react-app then I have a real treat for you! My handy cra-hyperapp project offers scripts to replace your react-scripts along with some helper functions for transitioning the majority of your app code gradually over to native Hyperapp. Here are some step-by-step instructions for how to make the escape into Hyperland.

Wrapping up

We have travelled a great distance on this journey together, but let’s not forget where it all started. Redux is an amazingly powerful functional programming library that has had an extraordinary impact on my programming philosophy. I have read the entire source code multiple times, which is very approachable and has taught me so much. There’s even a lesson in how to write a compose function properly!

The Redux docs are extremely well written, and have often guided me in my quest for functional enlightenment. The father of Redux (Dan Abramov) is one of the nicest people in all of open source, and always so helpful. He has released a series of free videos I can’t recommend highly enough for Redux users of all skill levels.

I have worked on large projects built with Redux, and I know that it can scale. The reducers and middleware code that we write have as close to 100% test coverage as we can possibly manage. Bugs in this code tend to be found quickly and fixed easily. If we didn’t have to write views then Redux would be pretty much the only tool we would use to build applications.

When it’s time to implement a view, I’ve previously reached for React because it was either rapidly growing or well established and frequently used together with Redux. Although pure functional components are possible to write, they are limited enough that in a larger app you will eventually need stateful class components with lifecycle methods and all the headache that entails. Tests will hit significant challenges also, particularly for those stateful components. Debugging errors is challenging, particularly when they involve tracing through the daunting source of React. Bugs often are hacked around instead of fixed, if they are even found at all.

This is what made me into a Redux refugee 🚁

I’m fleeing my functional Redux homeland not because I don’t love it there, but because of all the pain and suffering that the neighbors are causing me.

Hyperapp was my escape hatch into an alternate reality where the view can be just as functional as the state. Finally I could feel that same bliss I experienced part-time when writing the Redux parts of my app all-of-the-time. If you’re a Redux developer who like me is seeking a better balance between the simple functional data transformation world and the complex frontend imperative world, then I encourage you to give Hyperapp a chance.

Hyperapp was conceived by Jorge Bucaran. The project has been around for barely a year and already has an active, vibrant community from literally around the world contributing to and supporting it. In that first year Hyperapp claimed the #5 spot in growth behind only the “big three” established front end libraries and a smaller alternative to one of them.

Compared to the combined APIs of Redux and (especially) React, Hyperapp aggressively minimizes the concepts you need to learn to be productive. Hyperapp takes simplicity just as seriously as Redux does. In an effort to do more with less, the source code of Hyperapp is ~300 lines of approachable JavaScript that I can read when I have a question and debug when I have an issue. Here is the entire minified library that arrives in your browser as a cozy 1.4 kB gzipped response, just to make a point:

I am neither a Redux or Hyperapp expert, though I do contribute to the latter. If you spot a mistake or inaccuracy, leave me a comment or send your complaints to @okwolf!