Test code, not sanity

Simple testing simply made simple

Aug 3rd, 2018 · 3 min read

Simple is a word with a long and sordid history. The meaning has gotten watered down over the years to the point where today simple is used as a generic inoffensive term of praise. Let’s take a quick tour through some of the common connotations for simple that are used and see how they would apply to software testing.

easy

This is one of the more commonly used definitions of simple, and likely one of the most dangerous as well. Rich Hickey (Clojure’s benevolent dictator for life) gave an entire talk about simple vs easy, but to summarize: easy is subjective and simple is objective. This measure depends on individual ability and experience more than anything universally measurable. The ease of a task is inversely proportional to the effort and pain needed to accomplish it.

When applied to the world of testing, this sort of mindset leads to snapshot tests and similar approaches. While these are certainly easy to setup and write, I personally find them to be fairly low value. They are documenting and blindly trusting existing software implementations instead of specifying what the behavior of the software should be.

minimal

This definition is obsessed with the size and/or count of the software being evaluated. While these measures can be a proxy for simplicity, there are other far more direct ways by which to make this evaluation. This is the first meaning that has an objective measure which can be applied to compare approaches, which is a positive.

In the realm of testing this would lead us down a path toward using a single assert type function like Node.js already provides. The user would be responsible for running the tests and providing messages for troubleshooting in the event of failures. Other features such as a watch mode or code coverage would surely be left out entirely. Such tooling has become widely expected from test libraries. Ultimately users would end up creating their own ad-hoc test runner code that would be better written as part of a dedicated library.

untangled

This connotation directly derives from the etymology of the word simple:

From Middle English simple, from Old French and French simple, from Latin simplex (“simple”, literally “onefold”), from sim- (“the same”) + plicare (“to fold”).

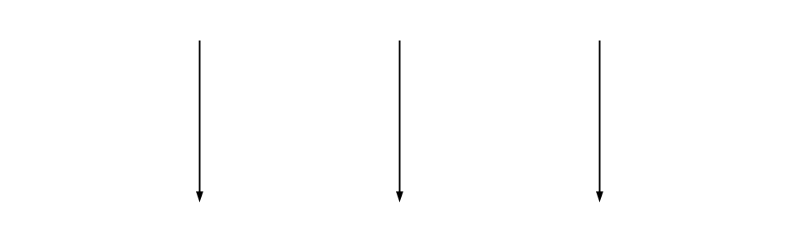

Rich Hickey strongly believes in this usage of simple and goes into great detail about it in his talk I linked earlier. To understand what we mean we begin with a diagram of a few straight lines:

Imagine the lines are software dependencies or threads of execution. It should be fairly obvious that these are free of tangles, and therefore simple.

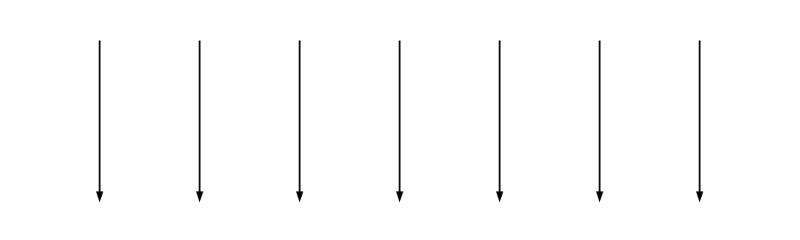

Now if we increase the number of lines but none of them overlap this is still simple:

It’s still possible to think about any one line independent of the others.

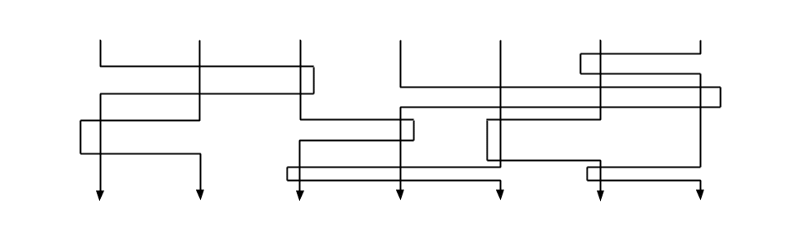

However if the same number of lines become tangled together then we have introduced complexity:

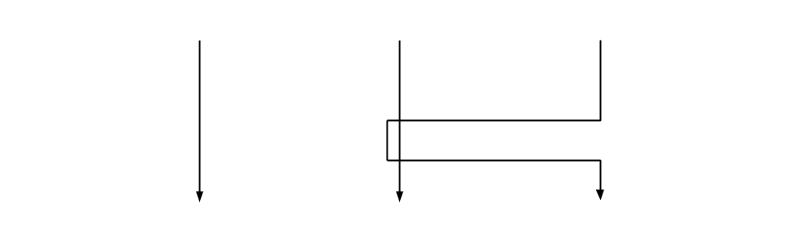

Decreasing the number of lines does not make this simple again:

It’s still not possible to reason about the second or third line in isolation without considering the impact the two have on each other. Avoiding tangles is an excellent goal to have for your software. It’s a necessary precondition for simplicity, but not a sufficient one. In order to fill in the missing blanks, we must take a look at the original definition of simple, and not just its etymology.

uncompounded

For the final usage of simple, we need to look at the technical dictionary definitions:

- (chemistry) Consisting of one single substance; uncompounded.

- (mathematics) Of a group: having no normal subgroup.

- (botany) Not compound, but possibly lobed.

- (zoology) Consisting of a single individual or zooid; not compound.

The common theme of these definitions is clear. If something can be broken down into parts that are independently useful, it can be made simpler by this meaning. Many best practices in project management around breaking down tasks into pieces that are digestible/understandable have related motivations. The concept is similar to the term atomic as it relates to computer science. Stuart Halloway (another major Clojure contributor) has his own talk on simplicity that covers this and other definitions of simple quite thoroughly.

While uncompounded is comparatively objective (similar to untangled), it is important to identify the proper level for evaluating simplicity. There are practical limits to the usefulness of this approach as applied to software generally and code in particular. Compilers and related tools introduce complexity but avoid thinking about programs at too simple of a level such as assembly, machine code, or even the underlying physics behind the processor.

Meeting this objective requires a rethinking of what fundamental elements should be used to build software. The Lisps of the world figured this out long ago by representing code as data. It’s difficult to think of a construct more indivisible than the list for representing code in a way that is still Turing complete. This moves the needle away from imperative code and toward declarative code. What if we could do something similar for our tests?

The answer to that cliffhanger is in my next article: